|

The Quest to Understand Mars

As long as humans have explored

the planets, from the time of crude telescopes through the age of sophisticated

robotic spacecraft, Mars has stirred great scientific and human interest.

As early as the mid-1600's, the astronomers Huygens and Cassini were able to note the planet's

major markings and determine its rotation period. Based on observations

of Mars between 1777-83, William Herschel suggested that Mars has a thin

atmosphere, polar ice caps, and seasons similar to Earth's. In 1877,

Schiaparelli

made detailed maps of Mars' surface and popularized the notion that long

canali, or channels, cover the surface. But it was nineteenth-century

astronomer Percival Lowell's description of an Earth-like Mars, criss-crossed

with long canals and covered with seasonal vegetation, that drew an intense

public interest in Mars (this drawing comes from his book Mars).

Lowell's books describing civilizations on

Mars were among the most popular scientific writings at the turn of the

century, yet many scientists of his day felt that he crossed the line between

science and science fiction. As long as humans have explored

the planets, from the time of crude telescopes through the age of sophisticated

robotic spacecraft, Mars has stirred great scientific and human interest.

As early as the mid-1600's, the astronomers Huygens and Cassini were able to note the planet's

major markings and determine its rotation period. Based on observations

of Mars between 1777-83, William Herschel suggested that Mars has a thin

atmosphere, polar ice caps, and seasons similar to Earth's. In 1877,

Schiaparelli

made detailed maps of Mars' surface and popularized the notion that long

canali, or channels, cover the surface. But it was nineteenth-century

astronomer Percival Lowell's description of an Earth-like Mars, criss-crossed

with long canals and covered with seasonal vegetation, that drew an intense

public interest in Mars (this drawing comes from his book Mars).

Lowell's books describing civilizations on

Mars were among the most popular scientific writings at the turn of the

century, yet many scientists of his day felt that he crossed the line between

science and science fiction.

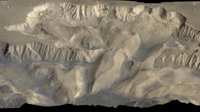

Ideas of civilizations and Earth-like

life were dashed when the first spacecraft to reach Mars revealed

a dry, cold, moon-like landscape. Mariner 4 flew

by the planet in 1965 and returned a few images of the southern cratered

highlands. Scientists noted how the spacecraft's radio signal diminished

as Mars passed between it and the Earth, calculating that Mars' atmospheric

pressure was 150 times less than Earth's. Mariners 6 and 7 in 1969 returned

many images that showed more varied landscapes. An infrared radiometer

found that the temperature of the south polar cap was 150 K (-193 F),

definitively

showing that it was composed of solid carbon dioxide, not water ice. In

1971-72, Mariner 9 conducted the first global mapping of Mars' surface

and atmosphere from orbit. A vast number of features and phenomena were

seen for the first time, revolutionizing the current view of Mars. Meanwhile,

the Soviet Union launched an ambitious series of probes to Mars with some

novel results, although all unfortunately prematurely failed.

The landmark spacecraft missions

to Mars were the pair of Viking Orbiters and Landers which arrived in 1976.

The orbiters mapped the entire surface at all seasons, measured the amount

and distribution of atmospheric water vapor through time, determined the

thermal properties of all surface materials including ices, and monitored

dust storms. Their discoveries included the fact that, unlike

the south, the north polar cap

was composed of water ice. The primary goal of the landers

was to conduct biology experiments designed to detect signs of past or

present life. No unambiguous signs of biological activity were found.

The landers also returned imagery and meteorology from the surface for

the first time. The landmark spacecraft missions

to Mars were the pair of Viking Orbiters and Landers which arrived in 1976.

The orbiters mapped the entire surface at all seasons, measured the amount

and distribution of atmospheric water vapor through time, determined the

thermal properties of all surface materials including ices, and monitored

dust storms. Their discoveries included the fact that, unlike

the south, the north polar cap

was composed of water ice. The primary goal of the landers

was to conduct biology experiments designed to detect signs of past or

present life. No unambiguous signs of biological activity were found.

The landers also returned imagery and meteorology from the surface for

the first time.

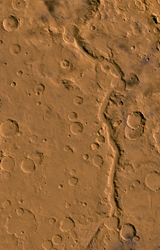

While these spacecraft did not find

aqueducts, civilizations, or even bacteria, they did find

signs of a past era that must have been quite different from the present.

The older highlands, which cover roughly the southern hemisphere of Mars,

are dissected by networks of valleys

that, although now dry, were probably formed by flowing water. In other

locations there is evidence for massive flooding, larger than any floods

on Earth, that carved wide paths through the landscape. The valley networks

and the flood channels flow into the northern plains of Mars, yet there

is no sign of the vast volumes of water that they once carried. Has this

water been frozen into an ocean beneath northern plains, locked in the

polar ice caps, or lost to space? Why was liquid water once so abundant but

now is completely absent? The Mars Polar Lander mission continues the

quest to understand Mars by addressing these and other questions left

unanswered by previous explorations. While these spacecraft did not find

aqueducts, civilizations, or even bacteria, they did find

signs of a past era that must have been quite different from the present.

The older highlands, which cover roughly the southern hemisphere of Mars,

are dissected by networks of valleys

that, although now dry, were probably formed by flowing water. In other

locations there is evidence for massive flooding, larger than any floods

on Earth, that carved wide paths through the landscape. The valley networks

and the flood channels flow into the northern plains of Mars, yet there

is no sign of the vast volumes of water that they once carried. Has this

water been frozen into an ocean beneath northern plains, locked in the

polar ice caps, or lost to space? Why was liquid water once so abundant but

now is completely absent? The Mars Polar Lander mission continues the

quest to understand Mars by addressing these and other questions left

unanswered by previous explorations.

|